This coming Wednesday, I am very thrilled to be joining the brilliant scholar Chiara Baldini in a conversation about A Different Kind of Power— the power held amongst the people, mountains and waters of pre-patriarchal Minoan Crete. This free webinar is in advance of a course devoted to Minoan history that Chiara is offering through Advaya this autumn. She is a wonderful scholar of the ancient Mediterranean, and her work on Minoan culture is an enormous gift— it is multidisciplinary, rigorous, feminist, embodied and passionate. I am both excited and honored to take part, for as so many of you know already, Crete is totally beloved to my heart.

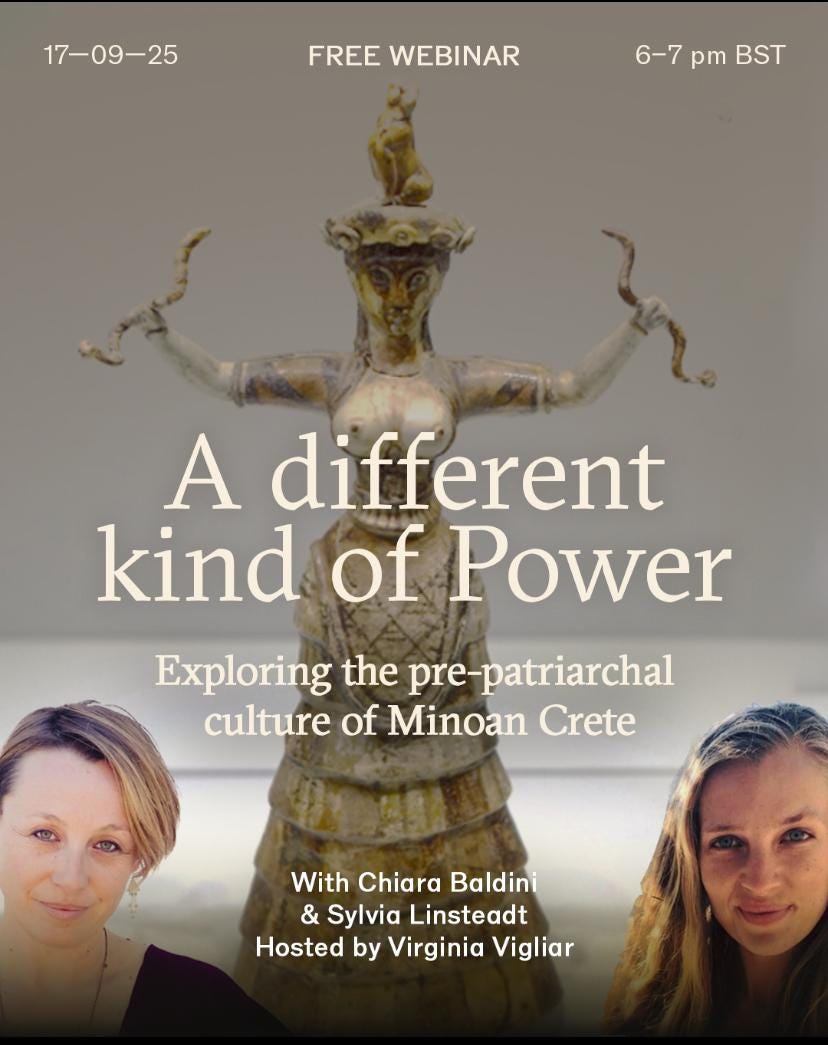

(Scroll down to the poster with the Snake Goddess to register for the webinar directly, or meander a bit more slowly there with me while I wax poetic about Crete for a few paragraphs first. And below all of that, I am offering —for my paid subscribers only— two storied glimpses from my novel fragments— “A Young Girl From the Hinterlands Visits Knossos in Spring,” and “A Cretan Priestess Recites Her Lineage.”

All these years ago now— seven, almost exactly this month— Crete caught me falling between worlds, between lives.

She caught me in her island arms where five-thousand year old altars and houses, roads and tombs rest under an open sky, where asphodel and poppies, mullein, mandrake root and wild oregano grow between the ancient stones in spring.

She caught me in her mountain arms raised up like the arms of the clay women buried in every holy cave and every shrine, every peak sanctuary and every precious grove from Kissamos to Zakros, from Heraklion to far Gavdos, her mountain arms furred with the forty herbs of childbirth, her mountain arms that are unafraid of earthquakes and that burgeon with clear-water springs.

She caught me between girl and woman, she caught me heartbreak after heartbreak, all three devastating but the first the worst of all. She knew just what to do with me.

She strung me like a warp on her loom and brought out her red thread.

She asked me to break open every part of myself that was hiding pain. She asked me also to devote myself to her story. To her many histories, to her healing plants, to her chapels where Mary still reigns supreme, to the ancestral mothers who came before Mary, all the way back to the Bird-Women at the beginning of the world, when the Pleiades could fly down and touch the Mediterranean Sea.

So I’ve been returning to my friends on the island these past seven years, both the human ones—the musicians and schoolteachers, environmentalists and artists, archaeologists and translators and weavers who have taken me in and taught me so much about life and soul and heart on every visit—and the mountain, cave, spring, and ancestor friends at special places across the island.

I’ve been studying the Greek language, and ruining my eyesight on small-print academic texts about Minoan history ever since, visiting archaeological museums across the island like they are my churches, and then again and again threading all that I am learning back through my pen and into my notebooks, where the fragments of several novels devoted to Crete are scattered, hundreds of thousands of words of them, waiting for me to become a slightly more expert archaeologist-of-my-own psyche in order to piece them together like an ornately painted offering vessel dug up out of five-thousand year depths.

During my last visit this past May, I went to my most sacred ruin on the island, a temple that was in use from the Neolithic until the Byzantine era. The spring still gushes out as cold as ice from beneath a great stone that was incorporated into the temple wall, cold enough to numb your hands in less than a minute. It must come from somewhere impossibly deep inside the mountain. Wild brookmint grows silvery from the seep, attracting bees to its purple flowers. Shepherds have the run of the mountainside now, and beekeepers with their tired, sugar-fed hives. The air is always full of the sound of goatbells. This time, when I put my hands and feet in the water, I heard clear as one of those bells in my mind the water say to me— you are a woman now. You were a girl when first we met, but you are no longer.

I am still turning those words over and over in my heart. Recognizing how, among other things, the loom Crete has re-woven parts of me upon has humbled me enormously. Tempered me— compassionately, but also unflinchingly. I think she is both loom and alembic, physician and dream-doctor, and has always been so, not just for me but for all pilgrims who have come to her shores.

Two thousand years ago, even in the Classical world, Crete was already known as an island of healing plants. Something about the soil made herbs grow more potent than anywhere else in the Mediterranean. Even the Romans said so.

And it is no less true now. We are still turning to Crete’s early history to understand a different kind of power than patriarchy. Both inside each of us, and in the world at large.

In this webinar, we will explore the topic of the upcoming course by Chiara Baldini on the Minoan culture of Crete. Who were the Minoans? Why can we define them as a pre-patriarchal culture? And why are they so important for us today?

After more than a century since the first excavations at Knossos, the Minoans continue to astonish with the mesmerizing beauty of their artistic production and the uniqueness of their religious and political systems, features that set them apart from other Mediterranean Bronze Age civilizations. In an increasingly patriarchal and warmongering world, where kings, warriors, and relationships of domination prevailed, the Minoans were able to carve a different path, with significantly less investment in weapons and armies and an impressive artistic production of pottery, frescoes, textiles, and jewelry. Their art reveals a unique spirit of creativity and skillfulness, a talent for grasping the sensual beauty of nature, a vibrant and ecstatic spirituality, and political structures that supported and encouraged such cultural richness.

Chiara Baldini, a scholar and cultural historian deeply versed in the study of Minoan society and spirituality, brings her expertise in tracing the threads between ancient myth, archaeological evidence, and contemporary relevance. She is joined by Sylvia Linsteadt, a writer and storyteller who lived for several years on Crete researching Minoan culture, and whose work braids myth, ecology, and feminist perspectives, making her uniquely attuned to drawing living meaning from ancient worlds. Together, their perspectives blend rigorous research with a sensitivity to story and symbolism, offering a conversation that is as intellectually grounded as it is imaginatively alive.

Join us for a conversation that will inspire minds to think beyond the patriarchal frame and hearts to feel that another world is possible.

CRETAN FRAGMENTS

1. A Young Girl From the Hinterlands Visits Knossos in Spring

My first visit to Knossos, most of what I remember is simply awe. The journey by boat from the harbor at Mochlos took an afternoon in fair weather, but because of my father’s death by sea I refused the water altogether, and insisted we join the pilgrims who made their way by land through the interior mountains. Grandmother patiently acquiesced to the two day journey by mule cart, and to a less-than-elegant arrival by land instead of the more suitable sea-arrival for a holy woman who had, after all, trained at the Great House of Knossos as a young woman.