Introduction

Once there was a queen who longed for a child while walking in an apple orchard and later gave birth to a red apple that hid a beautiful girl inside.

Once there was a woman who prayed for a child under a juniper tree while peeling an apple and then conceived .

Once there was a midwife who became a weasel who helped untie the knots of a difficult labor and brought the baby out.

Once there was a pregnant woman who craved parsley so much that she made a deal with a witch in order to eat some from her garden.

Once there was a highborn lady who ran wild the entire nine months of her pregnancy, refusing to come indoors, and then gave birth to her child amongst the sows.

Once there was a mother whose son was born the same evening, the same hour, the same minute as an otherworld foal.

Once there was a virgin who gave birth to the son of God in a cave surrounded by donkeys, goats and sheep.

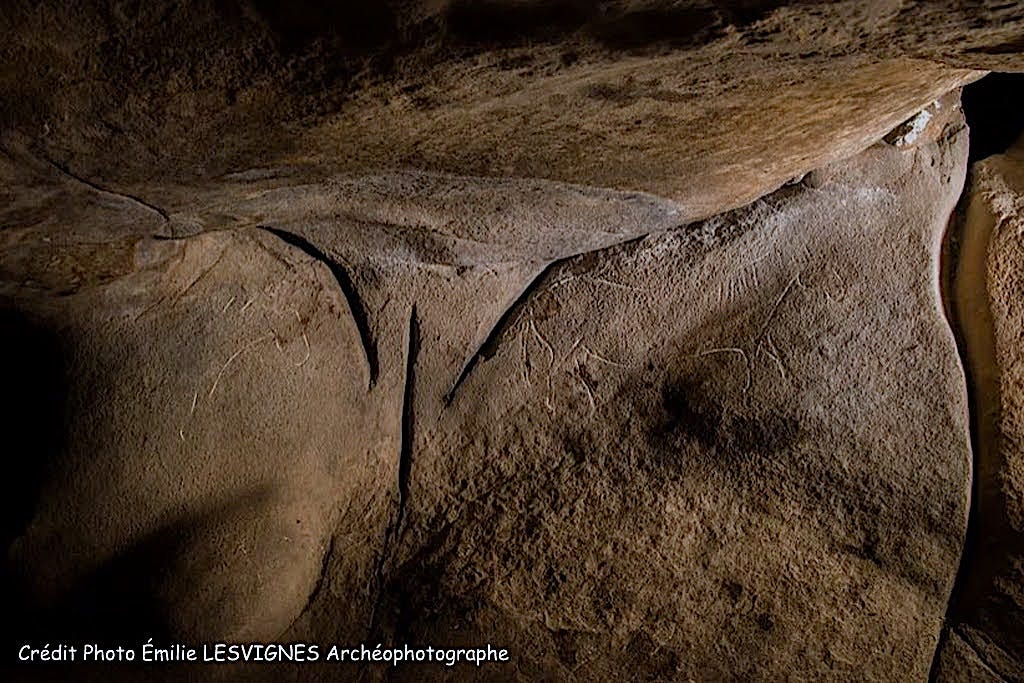

Once there was a cave in the Fontainebleau forest whose natural indentations resembled a vulva. Water ran there when it rained. Thirty thousand years ago an artist came with carving tools and made the story clearer.

Here was the beginning of the world: the vulva in the heart of the cave, and from it the first horses.

Welcome to Mother Animal: A (Growing) Anthology, a book project I will be sharing chapter by chapter with you on my Substack throughout 2024. Inspired by such anthologies as Angela Carter’s 1995 The Old Wives’ Fairy Tale Book, the idea for this project arose over the last year alongside my doctoral research.

I was driving around Somerset last April, listening to an audiobook about pregnancy and childbirth—long a topic of interest for me, far back to my girlhood when I was always reading novels about young midwives— when it first struck me. I couldn’t think of a single myth that treated the topics of pregnancy or childbirth with anywhere near the kind of airtime given to epic battles, sieges, man-to-man combats, long voyages, raiding parties, or elaborate hunts. And then, to my surprise, when I went looking I couldn’t find a single comprehensive study, and hardly any papers, that examined motifs of pregnancy and childbirth in the broader mythic or folkloric record.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m at the edge of my seat as much as anyone is about what will happen to Helen and Cassandra and Achilles and Paris and Agamemnon (not a fan) on both sides during the siege of Troy in the Iliad, and I’m riveted by long otherworld hunts for mythic boars and bulls and bears, and many-years journeys of piety and humbling in order to get back into the Grail castle and ask the right question. My heart soars and grieves and loves along with all of them.

But when I thought about the five very close female friends of mine who had all become mothers in the last years, and the detailed, passionate, harrowing, hallucinatory, unfathomably powerful birth stories I had heard from each of them, as well as the musings, reflections, cravings and visionary capacities that I witnessed in every single one of them before they gave birth, and then the unbelievably tenderizing, shattering, reconstituting, terrifying, raw, foundational transformations of the first months postpartum that they shared with me— I thought to myself: there’s no way that the women of ancient, traditional or indigenous cultures didn’t (or don’t still) have epics of their own about the incomparable journey of giving birth.

The stories I’ve heard my friends tell are the most incredible, intense, riveting tales I’ve ever been told. And there is a profoundly oral quality to a birth story. While I’ve read them recounted in Ina May Gaskin’s Spiritual Midwifery and other such places, there’s something about a woman’s birth story that almost requires orality, that requires bodily presence to be told most fully, and to be received.

So surely, I reasoned, if there have been so many stories crafted and told that have inspired heroism in men, there should be equally as many stories that have inspired courage and strength in women in childbirth. Surely this would have been part of the long-ago repertoire of a midwife, and of the elder matrons in a woman’s life. And surely, in a culture that centered life and birth, not death, it wouldn’t have only been women who would have wanted to hear the tales of courageous childbirths where the laboring mother flew to the stars and back, to the underworld and back between contractions to retrieve her child? Surely, everyone would have been riveted, because it’s how we all got here.

We say men returning from the hunt to the fire were the first storytellers, with their tales of mammoths and near-death encounters, but what if women in childbirth were too? What if they both told their stories around that primordial fire, and were received with equal awe and reverence?

So, my intention with this anthology is to pursue this question—where are the traces of these stories to do with childbirth in the mythic and folkloric record? Are they embedded in cosmological creation myths? Are they metaphorically embedded in female epics like Inanna’s descent, Ariadne’s giving birth in the underworld?

And most of all, what might the motifs of conception, pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum that we do find countless flashes of in extant folktales, fairytales and myths tell us about the deep collective understanding of this wombic process, the creation story of us all?

Mother Animal will be their gathering place, a field for the great matriarchal herds of elk to come grazing. It will be primarily a collection, a reference point, a book you can flip through to get a sense of the breadth of imagery and motif. Of course it won’t be comprehensive (that would take a decade at least!) but I hope it will be enriching.

In many ways I’m embarking on this adventure because this is the book I long to have in my hands if I become a mother myself. A kind of soulful preparatory text to go alongside all the more practical volumes. This is the book I wish to give to my friends who also want to become mothers, or who are sisters to mothers, or friends to mothers, to my friends who are already mothers, and to anyone who might want to engage with concepts of pregnancy and birth in new, enlivening, empowering ways.

I hope also that this book can offer a different kind of blueprint about the creative process itself, one rooted in metaphors that arise up through the body, or from the earth into the body, instead of Muses that descend at the beck and call of male poets down through the head.

This is a collection whose spirit is open to all, both in gender, in interest and in birth experience. And it’s important to emphasize that the title and subject matter, with its celebration of the mammalian power of birth, doesn’t mean that I subscribe to any one kind of birth. My friends, my mother, my grandmothers, have had every kind of pregnancy and birth imaginable, from totally wild and free with no interventions, to C-sections and all other necessary allopathic procedures. I have literally no judgements here of any of these stories, they are entirely equal to me in courage and beauty. I have only an enormous celebration, awe and desire to honor these experiences so fundamental to our collective human psyche by offering a resource for the soul and the heart, a reclamation of pregnant folk memory and mythic knowing hidden in plain sight in our stories for millennia.

I hope that this collection feels like a gathering in, a celebration, an enormous armful of riches—as the oldest sense of the word anthology carries, from the ancient Greek ἀνθολογία: “a collection of flowers,” from ἄνθος, flower—a garland of prophylactic herbs to wear around your head, your neck, your belly.

Finally, I want to dedicate this work in this season not only to my own mother and her mother and my motherline back through generations, and not only to my beloved friends who are mothers, but also to the women in Gaza who are having to give birth and mother their children in unthinkable circumstances right now. Women who are having to give birth in a warzone, in terror, with not only none of the life-saving supports of modern medicine that are sometimes needed, but also none of the herbal support, midwife support, safe, warm, surrounded-by-women you trust in a protected-den support that are crucial for the physiological processes of birth to take place safely and humanely.

Yesterday I read the story in the Middle East Eye of a 28-year old Palestinian woman named Fedaa Issa who was six months pregnant at the time of the first Israeli notice for her and her family to evacuate their home. She began to bleed heavily twenty minutes into their flight, forcing them to take refuge at a friend’s house. A week later the house was surrounded by shelling, and so she was forced to leave again. Eventually she made it to Kamal Adwan hospital in the south.

“I walked through the wounded and bleeding. They had no doctors to treat them. Pregnant women were giving birth, screaming in labour, with no midwives or anesthetics available for C-sections. These women were giving birth in hellish scenes, with dead bodies scattered all around them,” Issa told the Middle East Eye. These hellish scenes prompted her and her family to flee further south again, crossing through military checkpoints where Issa was forbidden to sit down though she was visibly pregnant and had started to bleed again, and was also robbed of everything she carried. Miraculously, she and her family made it to relative safety after that, and she gave birth on December 2nd, almost a month early, by cesarian section with only partial anesthesia.

This is for you Fedaa Issa, in all of your mother animal dignity. For all the mothers and babies in Gaza who have not survived their labors. For the mothers who are giving birth even as I type. May your children thrive in a world that knows peace and liberation once more. I honor your courage and your love, which are the courage and love of the Mother of us all.

LABOR PAINS by Fadwa Tuqan The wind blows the pollen in the night through ruins of fields and homes. Earth shivers with love, with the pain of giving birth, but the conqueror wants us to believe stories of submission and surrender. O Arab Aurora! Tell the usurper of our land that childbirth is a force unknown to him, the pain of a mother's body, that the scarred land inaugurates life at the moment of dawn when the rose of blood blooms on the wound.

-translated by Kamal Boullata

1.

The Zōon“Plato’s Timaeus is often cited for its famous description of the uterus as a zōon (Ti. 91c), a “living animal” that roams around the interior of a woman’s body with a desire for childbearing.”

-from, “Animal Wombs: The Octopus and the Uterus in Graeco-Roman Culture,” by Anna-Bonnell Friedlin, in Classical Philology 116 (2021), by The University of Chicago

According to a classical Greek gynecological claim popularized by Hippocrates—whose shadow reached well into the 20th century in Freud’s Studies on Hysteria, and even shows traces in contemporary obstetrics units— we women have animals moving around in us. Womb-animals, to be precise. Favorite animal comparisons have included octopuses, toads, hedgehogs and weasels. These animal uteruses — these zöon —supposedly influenced the way women felt, thought and by extension imagined, created and lived.

Wombs hosted inner demons, according to Roman ritual exorcists of the early Christian era (exclusively male) who claimed they could banish them. While it was understood even at the time that there was scientific basis for this belief, and it was debunked by doctors in Alexandria not long after the era of Plato, it still stuck, and has continued to exert its influence in all manner of misogynies and oppressions over the ensuing two millennia.

But such a belief, such an accusation—to be the sex who harbors so-called demonic animals under her skin—is only oppressive within a culture system that values the human over the animal, culture over nature, intellect over bodily knowledge, male over female.

A quick survey of indigenous literatures and mythologies the world over, and in fact the remnants of such thought-systems still hidden within folktales, fairytales and myths in the European west, will swiftly complicate these hierarchies, and offer up instead such classics as “The Woman Who Married A Bear,” an Alaskan Tlingit tribal story brought to western attention by Gary Snyder in his Myths and Texts and later The Practice of the Wild, in which a woman does as the title says. She falls in love with a bear, grows fur, has bear cub babies, and eventually goes back to her human settlement not as a demonic figure but as a kind of founding mother, culture heroine, and bridge between peoples— human people and bear people.

This mythic and folkloric motif of women either marrying animal husbands or birthing animal children, or displaying animal characteristics after giving birth, namely by cannibalizing their children (as wild animal mothers sometimes do when they’ve experienced trauma during or shortly after giving birth) is in fact widespread in the European fairytale and mythic tradition as well— from Pasiphaë wife of king Minos of Crete who according to classical Greek myths fell in love with a white bull, mated with him, and gave birth to a monstrous child, the Minotaur, to Rhiannon wife of king Pwyll of Dyved in the medieval Welsh Mabinogion who bears prominent links to horse goddesses, and on the eve of her labor has her child stolen, is betrayed by her midwives and accused of cannibalizing him.

And while very often in these stories this animal nature or animal instinct in the female protagonist is demonized, it points to an underlying reality that cannot be easily escaped or erased, however much we’ve tried— that sexual intercourse, pregnancy and childbirth are inherently mammalian. They are experiences governed, scientifically speaking, by basic hormonal and physiological processes shared to a great degree by most female mammals, and certainly by all female humans.

“[…]the surplus of animal presences in the witches’ lives also suggests that women were at a (slippery) crossroads between men and animals, and that not only female sexuality, but femininity as such, was akin to animality. To seal this equation, witches were often accused of shifting their shape and morphing into animals, while the most commonly cited familiar was the toad, which as a symbol of the vagina synthesized sexuality bestiality, femininity and evil”

- from Silvia Federici’s Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, page 216

But what would it look like if this story of the uterus as zöon, and the woman as harboring this animal other—not just while pregnant but in fact all the time she’s walking around with a reproductive system, or the memory of one in her bones and ligaments even if she doesn’t have one anymore—were to be taken as an empowerment and not an oppression? What does it mean to reclaim both animal interior, animal instinct, and the workings of a female biology not as inferior or defective but as distinctly noble and equal, and possessing of its own unique and precious language?

As Cristina Mazzoni writes in her Maternal Impressions: Pregnancy and Childbirth in Literature and Theory, “Knowledge of pregnancy represents, metonymically, knowledge of one’s body, as literary texts repeatedly imply: a problematic knowledge that can only be communicated to those who have experienced it themselves. Not husbands, then […] but other mothers, often embodied by an older, more experienced woman who, like Rapunzel’s enchantress, helps the protagonist decipher the nature of her otherwise incomprehensible sensations. Bodily knowledge, pregnant knowledge is in these texts preverbal, semiotic, based on an internal touch” (81).

May this collection offer something like that older-woman storytelling in Rapunzel. I’m looking to her to guide me as I go along my foraging journey for all of you. May this internal touching, this gathering in of women under apple trees and women swallowing juniper berries and women birthing among white sows and women suckling wolf cubs, offer a songline of pregnant knowledge. Pregnant knowledge is, after all, animal knowledge. It’s old, evolutionary, mammalian instinctive body-spoken knowledge. It’s universal to humankind. It’s as primordial as the carving on the cave wall of Fontainebleau. More so, even.

And if ever there was a time when we needed both animal knowledge and pregnant knowledge, knowledge of the ground of life and the laws of earth, now, I daresay, would be that time.

So let’s follow those hedgehogs and octopuses, those beautiful weasels and frogs, out into the wild, and in….

To Be Continued in monthly installments, the next on February 18th 2024 with a closer look at the Paleolithic and Mesolithic, both stories in stone and ochre, and traces of animal mothers, animal children & cross-species nursing in the oral tradition.

Note that all future issues of MOTHER ANIMAL will be for paid subscribers only, so if you would like to be part of this journey and to support this work, you can do so for the cost of just one fancy pot of tea per month!

In between, mid-month, I will continue to share writings and musings about my place-in-space, with land notes, personal notes, song notes, as the spirit guides me, all united by their attention to the seasonality and ecological realities of the place on earth where I find myself— in the continued spirit of my Year’s Wife writings.

News & events—

Places are going fast in my Swan Stories Workshop on Vancouver Island this March 2nd & 3rd, taught with dancer Nao Sims. I’m so excited to be leading an in-person immersion again! See here for more.

In addition Nao’s next dance series, which is dedicated to the Six Swans fairytale, starts tomorrow (both in person and on zoom)! If you want to hop in, now’s your chance :) I’ll be teaching a writing workshop as part of it on February 17th. Email Nao at naoisobel@gmail.com to register.

Finally, if you want to sink in more to the world of our collaboration, Nao and I have recorded a conversation which is now live on my podcast, Kalliope’s Sanctum.

Listen here :

This is so exciting! Looking forward to keep reading!

You know, the quote you share about the zoon ... here in Brasil some women* until now a days talks about the "mother of the womb" or the "mother of the body" who misses the baby who was inside the pregnant body and needs to be tendered and well fed not make the new mother sick. I loved to discover that this idea it's spread all over the world.

*it's indigenous knowledge and became folk history. In the north of Brasil more popular still. But usually now it's more kind of a "my granny used to say", you know? But not forgotten.

And also, I loved all the women you started to talk about in the beginning, all the "once there was". I fell like I want to meet them all, know all their histories!

Thank you, thank you! The world needs this work of yours so very much! I’m reminded of Marija Gimbutas’ work, particularly of the hedgehog, frog, and fish epiphanies of The Goddess of ancient Europe: the Divine Womb. Like the snake, what once was divine has been recast as evil, but the truth is still there, waiting for us to uncover and remember. The animal inside us is our divine guide through the utterly physical experience of birth. Also, you probably have it already, but Italo Calvino’s anthology of Italian folktales is full of barren women praying for a child, then giving birth to a plant, a chicken, or some living creature that upon closer inspection is one of the life-force symbols abundant in pre-Indo-European sacred pottery, paintings, and carvings. There is always so much more to the story! I am looking forward to reading your exquisite explanations of what you are finding!